| If you do

NOT see the Table of Contents frame to the left of this page, then

Click here to open 'USArmyGermany' frameset |

|||||||||

|

Military Police Units |

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

| Military Police Units | |||||||||

|

822nd MP Company 7751st MP Group (Customs) 11th MP Detachment (CI) Checkpoint Bravo Confinement Facility * (759th Military Police Battalion on a separate page) |

|||||||||

| 272nd Military Police Company | |||||||||

272nd MP Co guard mount before beginning patrol, 1950s |

|||||||||

272nd MP's working with West Berlin police, 1950s |

|||||||||

| 287th Military Police Company | |||||||||

287th MP Company sign at Andew Barracks, Berlin (Michael Stopienski) |

|||||||||

287th MP Company helmet 287th MP Company helmet |

|||||||||

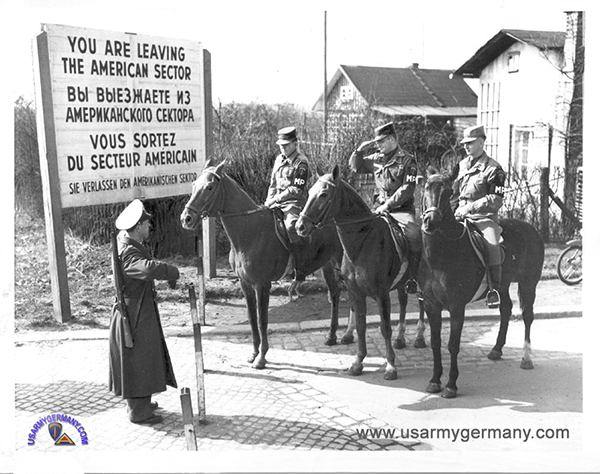

| 287th MP Co. is reconstituted for active army service [?] in Oct. 1953, as the 759th MP Bn. is deactivated.

Together with the 272nd MP Company, the 287th assumes the law enforcement mission in occupied Berlin. On Mar. 31, 1958, the Horse Platoon, previously assigned to the 287th MP Co., is deactivated in Berlin. On Jun. 1, 1958, the 272nd MP Co. is deactivated leaving the 287th as the sole American Military Police unit in Berlin. Concurrently, the 287th MP Co is designated a "separate unit." In Aug/Sept 1961, a small detachment of the 287th MP Co. is set up in Steinstuecken, a political enclave associated with West Berlin In Oct. 1961, one platoon from the 385th MP Bn, stationed in the FRG, is attached to the 287th for duty at Checkpoint Charlie. In Oct 1961, elements of the 287th MP Co. are deployed to the Friedrichstrasse crossing point during the Soviet - US sector border confrontation. |

|||||||||

Final patrol, Horse Platoon, 287th MP Company, 1958 |

|||||||||

| (Source: Horse Platoon patch and photos provided by Robert Wuhrman; Robert's father served with Horse Platoon in the mid-1950s) | |||||||||

Horse Platoon, 287th MP Co, SSI Horse Platoon, 287th MP Co, SSI Horse Platoon, 287th MP Co, DUI Horse Platoon, 287th MP Co, DUI |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| 1954 | |||||||||

| (Source: Army Information Digest, May 1954) | |||||||||

| Patrol along

the Iron Curtain with All the Army's Horses By Lt Frank W. Richnak First Lieutenant Frank W. Richnak, Military Police Corps, is Commander of the Horse Platoon, 287th Military Police Company. |

|||||||||

| Fifty-seven horses

located one hundred miles behind the Iron Curtain in Germany, and

the thirty-seven American men on duty with them, constitute the last

remaining horse unit in the United States Army, and probably the only

mounted outfit of its type left within the United States Armed Forces. The Berlin unit which includes all the Army's horses and some of its men, is the Horse Platoon of the 287th Military Police Company, an integral and colorful segment of the Military Police organization within the Army's Berlin Command. Riding and caring for the last of the present-day Army cavalry are thirty-seven "spit and polish" soldiers. Under the operational control of the Berlin Command Provost Marshal, the unit has become a showpiece after nine years of service. Although the Horse Platoon is in no sense an official Army cavalry unit, it serves to some extent as a present-day link with the tradition of the old US Cavalry and such legendary figures as Generals Custer, Stuart and Sheridan. Activated originally in October 1945 from men and horses drawn from the 78th Cavalry Reconnaissance troop of the 78th Infantry (Lightning) Division, the unit was designed to serve as an honor guard, escort platoon, and as a ceremonial element at reviews and other military events. Horses and men arrived in Berlin for duty in January 1946 and in May of the same year the unit was integrated with the 16th Constabulary Squadron. When the Constabulary passed from the Army occupation scene late in 1950, the Horse Platoon wan transferred to the 759th Military Police Battalion and with the deactivation of that organization the riders and mounts became part of the 287th Military Police Company. |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| An aggressive

mounted training program is followed in addition to normal training

with dismounted troops. Included in the mounted training are bareback

riding, jumping over small obstacles and the use of special weapons

such as tear gas grenades and 29-inch riot sticks together with carbines

and pistols. The horses are put through their training amid the various

types of noise that might be encountered during a riot. Considerable

attention is devoted to reconnaissance patrol training in the Gruenewald

Forest, a wooded area near the border that separates the American

Sector of Berlin from the Soviet-occupied Zone of Germany. A special sideline activity of the Berlin Horse Platoon is its appearance and competition in Allied military horse shows. The platoon's former First Sergeant and instructor, Thomas Lee of Shreveport, Louisiana, won more than one hundred prizes competing against the cream of French and British riders and their mounts in recent years. All the men in the unit are volunteers, and were assigned originally to Military Police units in the US Army, European Command (USAREUR.) Most of them had civilian experience as professional horsemen, ranch hands or exercise boys. The platoon is quartered separately from its parent company and operates its own mess at billets near the stables in the southern edge of the American Sector. In the same area are the stables of the American Riding Association of Berlin whose members engage in recreational riding and inter-Allied horse shows. A large indoor arena is available for inclement weather use by both the Association and the Horse Platoon. A typical day with the platoon includes lessons in the care and grooming of horses, jumping practice, parade techniques, formations and exercising. Athletics such as baseball and wrestling matches -- with the men mounted on horses -- are organized frequently. Such contests are considered excellent training for men and animals alike. A popular training exercise is the equitation drill. In this activity a trooper puts his horse through a series of figure eights and similar maneuvers while the other men watch and judge each performance. Horses and men also must learn and continually practice drill quite similar to the dismounted type given to foot soldiers. The average age of the horses is ten years, and all recent additions have been selected from choice German stock. Only two of the animals are of American origin; they arrived in Europe with the 1948 United States Olympic equestrian team. The Horse Platoon has become such an established Army institution in old Berlin that many Berliners and Americans maintain the famous city will never be the same should the smart Military Police troopers ever lose their horses to some less romantic mode of transportation. |

|||||||||

One of the over 400 signs indicating the end of the American sector |

|||||||||

| 1976 | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

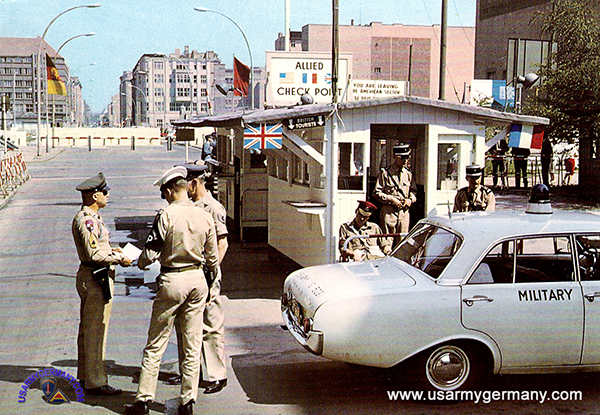

| Checkpoint Charlie | |||||||||

| 1945 - 1980 | |||||||||

| (Source: "Checkpoint Charlie ", Pamphlet 870-1, US Command, Berlin and US Army, Berlin, 1980.) | |||||||||

USCOB/USAB

Pam 870-1 Checkpoint Charlie |

|||||||||

Military

History Branch, G-3 Division Headquarters US Command, Berlin and US Army, Berlin |

|||||||||

1980 |

|||||||||

| 1. Introduction In the 19 years since Checkpoint CHARLIE came into being, virtually overnight, events have endowed the area with a dramatic mystique. It has been the scene of historical events and continues, in fact, to have a high potential for incidents. However, like the Wall itself, the drab physical reality of the Checkpoint area is in striking contrast with the dramatic situations of the Wall-crisis era. The Checkpoint itself, and the evolution of its operations, were an integral part of Allied responses to events. Basically, it is the mission of the Checkpoint, and the personnel of the Berlin Brigade's 287th Military Police Company who man it, to support the exercise of Allied rights in Greater Berlin. On a daily basis, they enforce U.S. regulations governing official travel to the Soviet (East) Sector of Berlin. They brief individual travelers and generally carry out policies intended to minimize the possibility of involvement by U.S. personnel in incidents, such as might have political repercussions. The history of Checkpoint CHARLIE is the history of events which, in the first place gave rise to a U.S. Army facility in the middle of Friedrichstrasse. An account of the facility alone would be of technical interest only, like a description of a bare stage when no performance is in progress. The Checkpoint facilities came into being in response to a crisis situation so grave that the course of events largely overshadowed the implementing details. The following account is intentionally brief. It aims to keep the Checkpoint, insofar as possible, in the center of events. Excepting basic points relevant to the narrative, Checkpoint procedures and regulations governing travel to East Berlin have been omitted. These are dealt with principally in U.S. Army, Europe and U.S. Command, Berlin Regulations 550-180. Under these regulations, it is the responsibility of commanders, supervisors, sponsors and the individuals concerned to ensure that Berlin-based personnel and persons traveling to Berlin are fully informed before they enter the Soviet Sector. 2. Free Circulation - The Allied Legal Position The wartime London Protocols (1944-45) provided for the joint military occupation of Greater Berlin. The agreed geographic and jurisdictional bases for the Protocols were the boundaries of Greater Berlin as defined by German Law in 1920. The right of free circulation for members of the respective forces, in all four Sectors, was inherent in the concept of joint occupation. In the early years of the occupation it had been repeatedly confirmed by Four-Power agreements, and by implementing arrangements and precedents having the force of Four-Power agreements. The significance of the Wall, then, was twofold. The human tragedy of the Wall, which, as it snaked across the city, walled up houses and stores and separated families, is well known. Its legal significance to the Allies, constrained to maintain their rights in order to fulfill their guarantees of continued freedom and democratic process to the people of Berlin, is less well known. The legal significance of the Wall was that it imposed, or sought to impose, among other things, a unilateral limitation on the Allied right of free circulation. In general, the Allied response to Soviet efforts to force them out of Berlin was to insist on their legal rights. This meant that the situation created by Four-Power agreements could not be changed except by the same means, agreement of all Four Powers. The Soviet Union (or its "agents", i.e. the East Germans) could not legally impose new restrictions on the exercise of Allied rights in Berlin unless the Western Allies agreed. Thus it was Allied policy to oppose as illegal Soviet-East German attempts to do so. The Wall -- that is, the sealing of the Sector-Sector (S/S) boundary and the beginning of construction of the Wall -- was a major unilateral change which, had it not been vigorously opposed, would have significantly restricted the Allied right of access to East Berlin. This threat to Allied rights, combined as it was with a significant worsening of conditions for the people of Berlin, was correctly understood as a further peril to the continued democratic existence of the Western Sectors of Berlin. 3. The Friedrichstrasse Crossing Point The boundary between the Western Sectors and the Soviet Sector is some 28.5 miles long, the so-called S/S border. From July 1945 to mid-August 1961, "free circulation" closely approximated what the term implies. For occupation purposes, the division of the city among the World War II Allies had been by administrative district (Bezirk). Thus the S/S border wound its way in a generally north-westerly direction, following the jurisdictional lines laid down in 1920. Near the center of this boundary the heart of the old city, "Berlin-Mitte", formed a westward salient of the Soviet Sector, which included the Brandenburg Gate. "Crossing Points" followed the main streets, the arteries of traffic. Before the war, more than 120 streets crossed the imaginary line drawn in the London Protocols. In early August 1961 some 80 crossing points remained open and passable in both directions. They were (relatively) lightly manned by East Germans and largely unfortified. Included in the 80 open crossing points were the Brandenburg Gate/Unter den Linden (east-west) and the Friedrichstrasse (north-south). In the pre-dawn hours of 13 August 1961, the East Germans sealed the S/S border and, during the ensuing days, began construction of the Wall. Initially, 13 of the 80 pre-Wall crossing points were to have remained open. During the ensuing ten days, mass demonstrations by West Berliners at the Brandenburg Gate gave the East Germans a pretext for closing it and five more pre-Wall crossing points. Only seven remained "open", subject to severe restrictions. Friedrichstrasse was one of them. After some initial uncertainties, the East Germans announced that Friedrichstrasse would be the only crossing point open to "foreigners", including West Germans, the Diplomatic Corps in East Berlin, and personnel of the Allied Garrisons. It was also to be an authorized crossing point for pedestrian traffic. Before the Wall, Friedrichstrasse did not differ significantly from other major crossing points. The street itself was rich in historic associations. It had been a main Berlin thoroughfare since the time of Friedrich Wilhelm (1713-1740), when troops of the Berlin garrison first marched along it to their training ground in Tempelhof. Under the German Empire (1871-1918) it had also been a main shopping street. It is probable, however, that purely practical considerations dictated the selection of principal crossing points. (Based on the sequence of events, it is possible that the East Germans first intended to keep the Brandenburg Gate open as a major crossing point, and changed their minds after the West Berliners had shown how suitable its broad approaches were for mass demonstrations.) Certainly there were several practical considerations which favored Friedrichstrasse as a main crossing point. Friedrichstrasse is a main North-South artery and the longest street in central Berlin. Absolutely straight and some two miles in length, it bisects the Unter den Linden, running from Mehringplatz in the U.S. Sector's Kreuzberg District to the Oranienburg Gate in Berlin-Mitte. In addition, the restored Friedrichstrasse Bahnhof, pre-war Berlin's main rail terminal, is barely a mile north of the S/S border and affords access to both the U-Bahn (subway) and the S-Bahn (elevated rail system), the city's main public transportation systems. The intention to make the Friedrichstrasse station the only point of entry into East Berlin for persons using the public transportation systems was announced the same day the border was sealed. The intent to restrict Allied traffic to the Friedrichstrasse crossing point was not announced until 22 August 1961, by which time, as noted above, the number of crossing points had been further reduced from 13 to 7. 4. Pre-Wall Controls Some controls on civil traffic existed before the Wall. The political division of the city occurred late in 1948. Apparently the Soviet authorities established, or provided for the establishment of the first control points on the S/S border at that time. In December of 1948, the Communist rump of the Magistrat (or city council) in East Berlin ordered that commercial vehicles from the Western Sectors would be required to enter East Berlin at these control points. By 1953, the number of crossing points passable in both directions had been reduced to about 80. Although information is spotty, there is no evidence of overt attempts to impose controls on traffic of the Allied garrisons. (In the absence of evidence to the contrary, we can only speculate on whether the Allies had, prior to the Wall, accepted some minor restriction of free circulation; where neither political fanfare nor systematic threat to the principle of Allied rights was involved, some local arrangements may have gained a kind of pragmatic sanction. Prior to 1961, the main arena appears to have been the surface access routes, not East Berlin.) Since pre-Wall controls were aimed at civil traffic, it is likely that the early control points were manned by East Germans. In September 1960, the East German regime introduced selective controls at the S/S border, restricting West Germans to the use of five specified crossing points. These early precedents, however, were of marginal significance when compared to the Wall, which marked a major turning point. 5. Significance of the Wall As tensions in Berlin mounted in the summer of 1961, so did the flow of escapees from East Germany and the Soviet Sector. In July and early August, the number of persons escaping into the Western Sectors averaged 1,800 per day; reportedly the high for a single day exceeded 3,000. From the standpoint of the Communist leadership in East Germany, the German Democratic Republic (G.D.R.) was, through massive losses of manpower, bleeding to death. West Berlin was the escape hatch, an open wound that had to be closed. The Wall was a Draconian measure to keep East Germans in. In a Four-Power context, however, it also marked a turning point. Prior to the Wall, Soviet authorities had often been uncooperative, themselves describing East Berlin as "the capital of the G.D.R.". In the days immediately preceding the Wall, the Soviet Government loudly repeated the long-standing (since 1958) demand for the withdrawal of the Allies and the conversion of the Western Sectors to a "free city". (The Soviets did not offer convincing proposals to guarantee West Berlin's continued existence as a democratic city.) In permitting the East Germans to seal the S/S border, and to attempt to impose controls upon the Allies, the Soviets added physical separation to the other means employed against the Allies, to force their assent to unilateral Soviet changes in the Four Power status of Greater Berlin. Despite steady Soviet-East German harassment, the Allies continued to exercise their rights in Berlin including the right of access to the Soviet Sector. The dramatic turning point in the dispute occurred in late October 1961. Intensified surveillance of the S/S border began on 13 August when it was sealed. The decision to restrict Allied traffic to a single crossing point quickly focused attention on the Friedrichstrasse area. Paralleling rising tensions and movement toward the U.S.-Soviet confrontation that almost immediately made it famous, the physical dimension of Checkpoint CHARLIE began to take shape. 6. Checkpoint CHARLIE The events of August 1961 dictated a requirement for a continuous U.S. military presence in the Friedrichstrasse area, where none had been before. The new situation at the S/S border was comparable to that which had long existed on the Berlin-Helmstedt autobahn, where single points of entry (or exit) gave access to the only route used by Allied motor-vehicle traffic. Allied Checkpoints at Helmstedt-Marienborn (between East and West Germany) and Dreilinden-Babelsburg (between the U.S. Sector and East Germany) supported Allied access and the exercise of Allied access right.* In the jargon of Army voice-communications, these autobahn checkpoint had long been called ALFA (Helmstedt) and BRAVO (Berlin). When the Wall created a new situation in the middle of Berlin and a third designated access point for the Allies, it immediately entered the Berlin vocabulary as Checkpoint CHARLIE. (Apparently, this was a logical and spontaneous extension of existing usage. At any rate, there is no known written record of a formal decision on what to call the new Checkpoint.) Unlike ALFA and BRAVO, intensive press coverage of events in the area gave "Checkpoint CHARLIE" an enduring place in the world's cold-war vocabulary. The East German measure to make Friedrichstrasse the only crossing point for foreigners, including the members of the forces in Berlin, went into effect at midnight on 22 August. During the ensuing days, combat troop of the three Allies screened the S/S border in their respective Sectors. Because of its location in the U.S. Sector, sole responsibiity for Friedrichstrasse was initially exercised by U. S. forces. An ad hoc detachment of U. S. Military Police began checkpoint operations in Friedrichstrasse on 23 August, in connection with the deployment of combat forces along the demarcation line. By 26 September, when heavier screening forces were withdrawn and thrice-daily patrols along the S/S border instituted, Checkpoint CHARLIE had become operational. *In 1969, a new link at the Berlin end of the autobahn was completed and the Soviet Allied Checkpoints were moved to their present location near Drewitz. On 1 September, U.S. authorities formally requisitioned space in the buildings on the West side of Friedrichstrasse in the block between Kochstrasse and Zimmerstrasse (which paralleled the actual demarcation line at that point). Number 207 Friedrichstrasse -- where travelers to East Berlin are still briefed -- and two rooms in the corner building at 19a Zimmerstrasse were allocated for use by U. S. Forces. According to a verified account, the first checkpoint operations were conducted from a desk in a U. S. Army semi-trailer placed in the middle of Friedrichstrasse in front of Number 207.* Probably the familiar white ("barracks style") structure had been set up in the middle of the street by mid-September. A rough-hewn, disproportionately large flag pole bracketed to the north end of the "shack" served to fly the colors unmistakeably near the Soviet Sector line. Although refinements were gradually added, the physical layout of the checkpoint area changed very little during the ensuing years.** During the first year of operations, official reports referred to the Friedrichstrasse crossing point or checkpoint, carefully avoiding local jargon in reports to higher headquarters. But the Checkpoint came into being literally overnight. During its first ten weeks in operation the level of greatpower tensions underlying the events that swirled around it was the highest in Berlin's post-war history. The news media gave intensive coverage to these events, in reporting them the press took their cue from the sign the Army put up over the door at No. 207 Friedrichstrasse. By 1965 the Friedrichstrasse area was in the guide books and, literally, on the map as Checkpoint CHARLIE. * British and French detachments were not continuously stationed at Checkpoint CHARLIE until 1962, as a result of efforts to harmonize Allied procedures and practices. (Intvw, Mr. K.M. Johnson, Berlin Command Historian with LTC Verner N. Pike, Cdr, 385th MP Bn, 27 Jan 77.) ** Although an extension to the south end provided working space for the British and French detachments, the original guard shack was in continous use for nearly 15 years. The outward appearance of the Checkpoint was changed very little by the prefabricated structure which replaced the original shack in May 1976. 7. Historical Highlights a. U. S.-Soviet Confrontation. The events of October 1961 catapulted Checkpoint CHARLIE into world prominence. The deepening crisis over the Four-Power status of Berlin endowed it with the lingering cold-war symbolism its name still evokes. Of the many dramatic events which occurred at or near the Checkpoint, the direct confrontation between U.S. and Soviet forces across the S/S border was probably the tensest moment in Berlin's post-war history. At issue was an East German attempt to deny free, uncontrolled entry into the Soviet Sector to civilian members of the forces in Berlin. They demanded that persons not actually in uniform identify themselves. Since status as members of the forces in Berlin derived from Allied laws agreed to by the Four Powers, and confirmed by long-standing precedents, the attempt to exclude civilian officials directly affected Allied rights. Then as now, "members of the forces", including military personnel, civilian employees and their dependents were prohibited from submitting to East German controls. The issues involved were complex and were not fully resolved until 1966. However, U.S. authorities in Berlin supported by General Lucius D. Clays* were convinced that East German attempts to actually deny entry into East Berlin could not go unchallenged. As a result, U. S. forces in the Checkpoint area were reinforced with tanks and armored personnel carriers (APC); one of the APCs and two tanks were positioned north of the Checkpoint building right at the S/S demarcation line. Beginning on 26 October, U.S. forces registered vehicles denied entry into East Berlin because non-uniformed personnel refused to identify themselves, were given an armed escort of jeep-mounted Military Police and sent back through the crossing point. Neither Soviet authorities nor East Germam police attempted to stop the escorted vehicles. By 1700 hours the next day, however, Soviet troops and armor had moved into position on their side of the S/S line. During the ensuing 24 hours, foreign and diplomatic travelers continued to move unmolested through the checkpoint. Until approximately 1100 hours on 28 October, Soviet and U. S. troops and tanks faced each other across the Friedrichstrasse boundary. At that time, both Soviet and U. S. forces withdrew into nearby staging areas on their respective sides. Inherent in the civilian-identification issue was the Four-Power status of Greater Berlin. The Western Allies insisted, in the face of Soviet disclaimers, that the Soviet Union remain responsible for its Sector. The firm U. S. position on the issue led to a Soviet demonstration, documented world-wide by the news media, of its ultimate responsibility for events in East Berlin. While the confrontation was in progress, General Clay called a news conference and pointedly announced the significance of the events then taking place: "The fiction that it was the East Germans who were responsible for trying to prevent Allied access to East Berlin is now destroyed. The fact that Soviet tanks appeared on the scene proves that the haressments. . . taking place at Friedrichstrasse were not those of the self-styled East German government but ordered by its Soviet masters". * The former U. S. Military Governor for Germany (1947-49), GEN Clay returned to Berlin in September 1961 as President Kennedy's personal representative with ambassadorial rank. b. Subsequent Events. Although the tense situation of 1961 was not repeated, Checkpoint CHARLIE continued to make news. Incidents related to the identification issue continued sporadically until 1966 when the present U.S. Forces Berlin identity document came into general use. Three days after the first anniversary of the Wall (17 Aug 62), the death of Peter Fechter some 100 meters east of the Checkpoint triggered mass demonstrations of West Berliners against the brutality of the East German Regime.* In the days that followed, crowds of West Berliners stoned Soviet buses as they brought their guard relief through Checkpoint CHARLIE enroute to the Soviet War Memorial in the Tiergarten (British Sector). In retaliation, the Soviets tried to bring their guard mount in with APCs. Ultimately, after a long series of incidents, Allied authorities prevailed upon them to discontinue the use of APCs, and to use the Sandkrug-Bridge crossing point, nearest their destination. The gradual decline of cold-war tensions in Berlin greatly reduced the number and severity of incidents at the Checkpoint. As recently as 1973, however, East German border guards opened fire with automatic weapons, hitting the Checkpoint building in several places. From the number and position of rounds that hit it, some going through windows and impacting in the inside walls, it was clear that only random chance had prevented injury to U. S. personnel. 8. Epilogue |

|||||||||

| * An East Berliner in his late teens, Fechter was trying to escape when he was shot and wounded by East German guards. They left him unattended at the base of the Wall, where he died some time later. His cries for help were clearly heard on the West Berlin side, but no one could get to him. He is probably the best known symbol of East German brutality at the Wall. | |||||||||

| COMMENTS

on Checkpoint Charlie A small clarification relating to events in September, 1962, provided by John Hehir who served as OIC at the checkpoint |

|||||||||

| I found the Checkpoint Charlie history document to be interesting

reading, especially since I served as OIC of the checkpoint for a

month at the end of 1962. One point in the history, however, was humorous. In Section 8, sub-paragraph B. "Subsequent Events", it says that the "Allied authorities prevailed upon them (the Russians) to discontinue the use of APCs, and to use the Sandkrug Bridge crossing point, nearest their destination (the Russian War Memorial on Strasse des 17 June). In fact, the manner in which the Allied persuaded them was by issuing an ultimatum that they could no longer cross at any other point and could not use APC's. To back up that ultimatum, the Allies sent small units to each of the major crossing points in the middle of the night (around American Labor Day). Those units carried live ammunition including grenades and 7.62 ammo and were charged with the mission of blocking their respective crossing points utilizing their vehicles and live ammunition as necessary. I headed up the unit which established Checkpoint Delta (the Heinrich Heine Strasse crossing point). Needless to say, this show of force had its intended effect and no ammunition was ever expended. Nevertheless, it clearly reminded me how serious (and potentially dangerous) the job of maintaining our rights and position in Berlin really was. |

|||||||||

Stand Off - US combat-ready armor at Checkpoint Charlie, early 1960s |

|||||||||

Routine day-to-day duty at Checkpoint Charlie, 1970s |

|||||||||

| (Source: BERLIN OBSERVER, Aug 31, 1990) | |||||||||

| Removal of Checkpoint Charlie in 1990 Several articles are presented that cover the removal of the Checkpoint hut and some history of the Checkpoint. |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||